16 March 1971

Trying to match Tommy, let alone even better it, was going to be no easy feat for Pete Townshend. Prior to the release of 7ft. Wide Car, 6ft. Wide Garage, he had envisioned a science fiction rock opera called Lifehouse, inspired from his experiences on the tour for Tommy where the vibrations in the crowd were so pure that he felt as if the world would just come to a stop, unifying the whole thing.

PETE TOWNSHEND: "The idea for Lifehouse was that it would be set in the future, like a fantasy where rock and roll music was banned, and the majority of the world's population lived indoors and were controlled by the government, wearing experience suits. Our hero, Bobby, would then broadcast music into the suits, giving the people the chance to take them off and become more enlightened." (1999)

To the people of today's world, this concept made sense, but in 1971, Roger Daltrey, John Entwistle and Keith Moon didn't understand Townshend's ambitious project. Wireless communication? Virtual reality? A Grid with a capital G? "That sounds totally alien, man," Daltrey commented. In return, Townshend had a frustrating time trying to articulate the concept. A series of concerts at the Young Vic theater in London were played in February for a proposed film adaptation of Lifehouse, but the experiment wasn't successful.

JOHN ENTWISTLE: "It could've worked out as Pete had said to us. The Beatles played at Woodstock and the Isle of Wight and presented material for the then-upcoming Get Back and that was a success. So he didn't know why the performances for Lifehouse didn't succeed as he had hoped." (1975)

The recording sessions began proper at the Record Plant in New York with a cover of Marvin Gaye's "Baby Don't You Do It" and with Glyn Johns as co-producer and co-engineer. The only other cover song included was Mose Allison's "Young Man Blues", actually a recording from 1968 that was left off of Magic Bus for reasons unknown. The track was reworked to better fit the 1971 recordings.

At least fifteen songs overall were recorded for Lifehouse over the next three months, but the initial sessions were plagued by manager Kit Lambert's heroin addiction and inability to produce the album. Coupled with Townshend's alcoholism at the time, it looked as though history was about to repeat itself with the Beach Boys' Smile and result in the death of Pete Townshend. He had spiraled into a nervous breakdown and even attempted to jump out of a hotel window in frustration.

ROGER DALTREY: "Pete really cared for the Lifehouse project like it was his child. Actually, no. It was his child, and we weren't doing much to help him bring it into the world. We had an album to finish, regardless if it was Lifehouse." (1988)

5 April 1971

GLYN JOHNS: "After that disaster where Pete nearly threw himself out the window, we relocated to Barnes to record new material and Kit Lambert was dropped from the project as producer. The sessions at Record Plant were satisfactory enough, though they did need a bit of tuning for the final release. Pete ended up giving up on the story for Lifehouse and reluctantly agreed to a more standard rock album." (2006)

Among the tracks being reworked was the future hit single "Won't Get Fooled Again", an eight and a half minute epic about a revolution that was intended to be the climax for Lifehouse. It would still be the penultimate track for the album despite the story being abandoned. Most of the original songs that ended up on Lifehouse - thirteen in total - were written by Pete Townshend; "When I Was a Boy" and "My Wife" were both by John Entwistle.

"Won't Get Fooled Again" came out as a single on 21 June with "Pure and Easy" as the B-side; the single charted at #9 in the United States and #2 in the United Kingdom, being kept off the top spot by the Ladders' "Bangla Desh/Imagine" double A-side. "Won't Get Fooled Again" had been cut down to three and a half minutes despite the band insisting that it be released in its full eight-plus minute glory. "We were more at home on albums than we were on singles," Daltrey remembered. (2001)

KEITH MOON: "We had so much material recorded for Lifehouse that we wanted to put it all out at once. John [Lennon] and George [Harrison] had both done so for Shine On, so why not The Who?" (1973)

13 August 1971

Despite abandoning the story for Lifehouse, much of Pete Townshend's concept actually ended up on the final album, and some fans ended up believing that the tracks had been arranged to form a loose yet intriguing story with a hard rocking climax. Some of those fans even believed that this was Townshend's intention for Lifehouse, but in interviews since the album's release, he has repeatedly contradicted himself as to whether or not it really was the case.

Whether or not Townshend's concept made the final Lifehouse release or not, it was still a commercial and critical success, reaching #2 in the United States and #1 in the United Kingdom for a week. In retrospect reviews, Lifehouse has been regarded not only as one of the Who's best albums, but one of the greatest albums of 1970s rock, let alone of all time.

That October, two singles were put out, one each for the United Kingdom and the United States. "Let's See Action"/"When I Was a Boy" was released in the former on the 18th, topping out at #14, whilst "Behind Blue Eyes"/"Baba O'Riley" came out in the latter country the week after, barely managing to reach #20. Of course, there was now the issue as to how their rivals of three years was going to respond to Lifehouse.

5 July - November 1971

MICK JAGGER: "Just as the Who were working on the final touches for Lifehouse, we were working on our first two albums under Apple Records. David had been working on a concept of his own about an androgynous rock star called Ziggy Stardust, whom he claimed was inspired by Lou Reed and Iggy Pop." (1983)

Despite the renewed success by bringing in David Bowie into their lineup, the Rolling Stones did not have the money owed to them prior to Allen Klein's death and were forced to become tax exiles and ended up living in France along with their families until their financial affairs were sorted. It was also where Mick Jagger would marry his first wife Bianca Morena de Macias. Paul and Linda McCartney, Eric Clapton, Stephen Stills and Dennis Wilson, among others, attended the wedding in St. Tropez.

This period away from England would inspire the title for the Rolling Stones' first Apple-era album, Exile on Mars. The initial period was a very fertile one for the Jagger/Richards duo and David Bowie, having penned around 30 to 40 songs in total. A triple album was considered, but it was decided instead to record two individual albums; one single-disc album and one double-disc album, the latter of which would be a rock opera.

KEITH RICHARDS: "After nearly a decade of being together, we're finally making a rock opera. Took us long enough." (1971, to the other members of the Rolling Stones)

The double album rock opera, tentatively titled Ziggy Stardust, featured the titular character as the main subject, with the first act showcasing his rise to stardom and the second would show his downfall from grace. Although it was being worked on at the same time as Exile on Mars (also titled for the Bowie song "Life on Mars"), the backing tracks for the latter album were finished up in August, with overdubs being worked on until November; by then, the full focus was on Ziggy Stardust.

During this period, David Bowie would make his appearance at the Concert for Bangladesh with "Space Oddity" and "Waiting for the Man" on 1 August, and on 21 October, Mick and Bianca Jagger would have their first daughter, Jade Jezebel Jagger. It was nearly three months after the birth of David and Angie's son Duncan Zowie Haywood Jones, born 30 May.[2]

10 December 1971

|

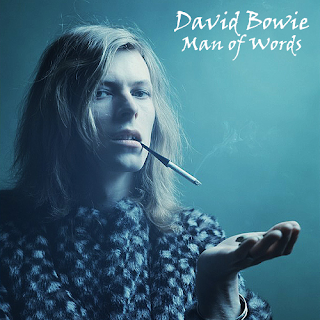

| Pete Townshend, 1971. |

PETE TOWNSHEND: "The idea for Lifehouse was that it would be set in the future, like a fantasy where rock and roll music was banned, and the majority of the world's population lived indoors and were controlled by the government, wearing experience suits. Our hero, Bobby, would then broadcast music into the suits, giving the people the chance to take them off and become more enlightened." (1999)

To the people of today's world, this concept made sense, but in 1971, Roger Daltrey, John Entwistle and Keith Moon didn't understand Townshend's ambitious project. Wireless communication? Virtual reality? A Grid with a capital G? "That sounds totally alien, man," Daltrey commented. In return, Townshend had a frustrating time trying to articulate the concept. A series of concerts at the Young Vic theater in London were played in February for a proposed film adaptation of Lifehouse, but the experiment wasn't successful.

JOHN ENTWISTLE: "It could've worked out as Pete had said to us. The Beatles played at Woodstock and the Isle of Wight and presented material for the then-upcoming Get Back and that was a success. So he didn't know why the performances for Lifehouse didn't succeed as he had hoped." (1975)

|

| The Who, 1971. |

At least fifteen songs overall were recorded for Lifehouse over the next three months, but the initial sessions were plagued by manager Kit Lambert's heroin addiction and inability to produce the album. Coupled with Townshend's alcoholism at the time, it looked as though history was about to repeat itself with the Beach Boys' Smile and result in the death of Pete Townshend. He had spiraled into a nervous breakdown and even attempted to jump out of a hotel window in frustration.

ROGER DALTREY: "Pete really cared for the Lifehouse project like it was his child. Actually, no. It was his child, and we weren't doing much to help him bring it into the world. We had an album to finish, regardless if it was Lifehouse." (1988)

5 April 1971

|

| Glyn Johns. The date of the picture taken is unknown, but it is believed to be around the early 1970s. |

Among the tracks being reworked was the future hit single "Won't Get Fooled Again", an eight and a half minute epic about a revolution that was intended to be the climax for Lifehouse. It would still be the penultimate track for the album despite the story being abandoned. Most of the original songs that ended up on Lifehouse - thirteen in total - were written by Pete Townshend; "When I Was a Boy" and "My Wife" were both by John Entwistle.

"Won't Get Fooled Again" came out as a single on 21 June with "Pure and Easy" as the B-side; the single charted at #9 in the United States and #2 in the United Kingdom, being kept off the top spot by the Ladders' "Bangla Desh/Imagine" double A-side. "Won't Get Fooled Again" had been cut down to three and a half minutes despite the band insisting that it be released in its full eight-plus minute glory. "We were more at home on albums than we were on singles," Daltrey remembered. (2001)

KEITH MOON: "We had so much material recorded for Lifehouse that we wanted to put it all out at once. John [Lennon] and George [Harrison] had both done so for Shine On, so why not The Who?" (1973)

13 August 1971

Released: 13 August 1971

Recorded: 19 September 1968, 16 March - 28 June 1971

Producer: The Who, Glyn Johns and Kit Lambert

Track listing[1]

Side A

Baba O'Riley

When I Was a Boy

Young Man Blues

Going Mobile

Time is Passing

Side B

Love Ain't for Keeping

My Wife

Too Much of Anything

Bargain

When I Was a Boy

Young Man Blues

Going Mobile

Time is Passing

Side B

Love Ain't for Keeping

My Wife

Too Much of Anything

Bargain

Side C

Pure and Easy

Baby Don't You Do It

Behind Blue Eyes

Put the Money Down

Getting in Tune

Side D

Let's See Action

Won't Get Fooled Again

The Song is Over

Baby Don't You Do It

Behind Blue Eyes

Put the Money Down

Getting in Tune

Side D

Let's See Action

Won't Get Fooled Again

The Song is Over

Despite abandoning the story for Lifehouse, much of Pete Townshend's concept actually ended up on the final album, and some fans ended up believing that the tracks had been arranged to form a loose yet intriguing story with a hard rocking climax. Some of those fans even believed that this was Townshend's intention for Lifehouse, but in interviews since the album's release, he has repeatedly contradicted himself as to whether or not it really was the case.

Whether or not Townshend's concept made the final Lifehouse release or not, it was still a commercial and critical success, reaching #2 in the United States and #1 in the United Kingdom for a week. In retrospect reviews, Lifehouse has been regarded not only as one of the Who's best albums, but one of the greatest albums of 1970s rock, let alone of all time.

That October, two singles were put out, one each for the United Kingdom and the United States. "Let's See Action"/"When I Was a Boy" was released in the former on the 18th, topping out at #14, whilst "Behind Blue Eyes"/"Baba O'Riley" came out in the latter country the week after, barely managing to reach #20. Of course, there was now the issue as to how their rivals of three years was going to respond to Lifehouse.

5 July - November 1971

|

| The Rolling Stones' logo from 1971 onwards, designed by John Pasche. |

Despite the renewed success by bringing in David Bowie into their lineup, the Rolling Stones did not have the money owed to them prior to Allen Klein's death and were forced to become tax exiles and ended up living in France along with their families until their financial affairs were sorted. It was also where Mick Jagger would marry his first wife Bianca Morena de Macias. Paul and Linda McCartney, Eric Clapton, Stephen Stills and Dennis Wilson, among others, attended the wedding in St. Tropez.

This period away from England would inspire the title for the Rolling Stones' first Apple-era album, Exile on Mars. The initial period was a very fertile one for the Jagger/Richards duo and David Bowie, having penned around 30 to 40 songs in total. A triple album was considered, but it was decided instead to record two individual albums; one single-disc album and one double-disc album, the latter of which would be a rock opera.

KEITH RICHARDS: "After nearly a decade of being together, we're finally making a rock opera. Took us long enough." (1971, to the other members of the Rolling Stones)

|

| The wedding of Mick Jagger and Bianca Morena de Macias, 12 May, 1971. |

During this period, David Bowie would make his appearance at the Concert for Bangladesh with "Space Oddity" and "Waiting for the Man" on 1 August, and on 21 October, Mick and Bianca Jagger would have their first daughter, Jade Jezebel Jagger. It was nearly three months after the birth of David and Angie's son Duncan Zowie Haywood Jones, born 30 May.[2]

Released: 10 December 1971

Recorded: July - November 1971

Producer: The Rolling Stones, Jimmy Miller and Ken Scott

Track listing[3]

Side A

Life on Mars

Sway

Kooks

Changes

Tumbling Dice

Quicksand

Side B

Happy

Bitch

Andy Warhol

Dead Flowers

The Bewlay Brothers

Soul Survivor

Sway

Kooks

Changes

Tumbling Dice

Quicksand

Side B

Happy

Bitch

Andy Warhol

Dead Flowers

The Bewlay Brothers

Soul Survivor

The first single off of Exile on Mars, "Changes" backed with "Happy", was released 6 December, reaching #15 in the United States but stalling at #2 in the United Kingdom, being kept off of the top by the Ladders' "Bangla Desh/Imagine". "Even on their label, we still struggle against the Beatles," Mick Jagger was believed to have said, but he has since denied the statement. Neither track was credited to Jagger/Richards or Bowie; instead, they were credited to the Rolling Stones as a whole, regardless as to who contributed what. "We all get equal royalties," Bowie explained. The second single "Tumbling Dice"/"Life on Mars", due out next year in February, would also be credited to all five members.

Exile on Mars reached the top of the charts in America and #2 in the United Kingdom; once again, left off of the top spot by the Ladders' Imagine. The album received positive reviews from critics, often being compared to the Beatles' 1968 self-titled release in terms of songwriting and performance. "Not only is Exile on Mars the Stones' most engaging album musically," Rolling Stone magazine wrote, "it also finds Bowie and the Glimmer Twins [Jagger and Richards] writing once more literally enough for the listener to examine their ideas comfortably, without having to withstand a barrage of seemingly impregnable verbiage before getting at some ideas."[4]

As 1971 drew to a close, the Rolling Stones were only just getting started for what they had planned for next year.

Footnotes

- Tracks are sourced from the following:

- Who's Next: "Baba O'Riley", "Going Mobile", "My Wife", "Bargain", "Getting in Tune", and "The Song is Over". "Love Ain't for Keeping" and "Won't Get Fooled Again" are alternate versions found on the 2003 reissue. "Pure and Easy" is a bonus track from the 1995 reissue. "Behind Blue Eyes" is the alternate version also found on the 1995 reissue.

- Who's Missing: "When I Was a Boy".

- Odds & Sods: "Young Man Blues", "Time is Passing", "Too Much of Anything", "Baby Don't You Do It", and "Put the Money Down".

- Thirty Years of Maximum R&B: "Let's See Action". It can also be found on The Who Hits 50!.

- Duncan Jones was born in Bromley, London in England, not France.

- Tracks are sourced from Hunky Dory, Sticky Fingers and Exile on Main Street.

- Actual review from Rolling Stone about David Bowie's Hunky Dory upon initial release, rewritten to reflect it being a Rolling Stones album.

Author's Comments

So here we are at the 25th chapter of the whole series; to celebrate this milestone, I give out the Strawberry Peppers take on the Who's ill-fated rock opera Lifehouse. The Lifehouse track listing was inspired by both of AEC's takes on the album either as a triple album including Pete Townshend demos or a double album with purely Who music. I went for the latter option and used the former's track listing as my template. I rearranged some tracks around after deleting what I'd already included on 7ft. Wide Car, 6ft. Wide Garage and included "Put the Money Down". The inclusion of that track is kind of questionable as it was recorded in 1972, but Wikipedia claims it was written for Lifehouse. Of course, I simply pretended it was written earlier.

As for the Rolling Stones' part of the chapter, there isn't much to say about it; it more or less follows what happened with them in OTL, minus the first dealings with Allen Klein (since he died in 1970) and with David Bowie involved for the ride. The next two chapters won't be very big; the 26th will focus on the leftover albums of 1971 that weren't on any of the previous few chapters, and the 27th will be about the solo CSNY projects of late 1971/early 1972.

Album cover for Lifehouse was made by IdesignAlbumCovers on Tumblr.

So here we are at the 25th chapter of the whole series; to celebrate this milestone, I give out the Strawberry Peppers take on the Who's ill-fated rock opera Lifehouse. The Lifehouse track listing was inspired by both of AEC's takes on the album either as a triple album including Pete Townshend demos or a double album with purely Who music. I went for the latter option and used the former's track listing as my template. I rearranged some tracks around after deleting what I'd already included on 7ft. Wide Car, 6ft. Wide Garage and included "Put the Money Down". The inclusion of that track is kind of questionable as it was recorded in 1972, but Wikipedia claims it was written for Lifehouse. Of course, I simply pretended it was written earlier.

As for the Rolling Stones' part of the chapter, there isn't much to say about it; it more or less follows what happened with them in OTL, minus the first dealings with Allen Klein (since he died in 1970) and with David Bowie involved for the ride. The next two chapters won't be very big; the 26th will focus on the leftover albums of 1971 that weren't on any of the previous few chapters, and the 27th will be about the solo CSNY projects of late 1971/early 1972.

Album cover for Lifehouse was made by IdesignAlbumCovers on Tumblr.